Space is Part of the Product: Using AttrakDiff to Identify Spatial Impact on User Experience with Media Façades

Publication

Abstract

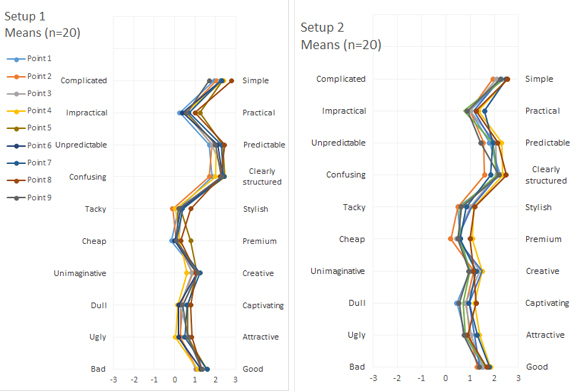

In HCI research, the user experience (UX) in response to interactive public installations, media façades and displays is frequently evaluated using the AttrakDiff questionnaire. The latent assumption is that its result is invariant to chang-es over time, environment and context. While previous re-search analyzed the impact of time as single variable, studies have not yet investigated environment or context. At the same time, researchers and practitioners appear to have the intuitive assumption that interaction with any media façade is best experienced from the middle at a distance which is ‘convenient’ to watch. We investigated the tem-poral, spatial and contextual impact on AttrakDiff’s user rated pragmatic and hedonic qualities and attractiveness. Analysis revealed that interacting from different positions in close vicinity (<15m) parallel to the media façade did not significantly influence UX. Ratings were mostly invariant when conducting the study at two different lived environ-ments; and short-timed repeated measures using AttrakDiff did not cause a decline in participants’ ratings.

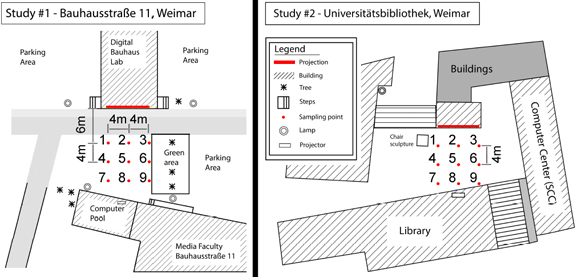

The figure above shows the spatial configuration of study situation #1 and #2.

Motivation

spatial configuration might influence user ratings of an interactive system. In fact, we argue public installations can be evaluated by using AttrakDiff, because they can be considered to a large extent being an interactive product. However, architecture and environmental psychology teaches us it cannot be so on a 100% level. We argue the spatial design of a public instal-lation is of UX relevancy for those too. In our opinion a public installation might be 95% a product and 5% architec-tural (spatial design). While the percentages might not be right, we use those to point out that AttrakDiff might be able to measure 95% of hedonic and pragmatic qualities, but missing out 5% of hedonic and pragmatic qualities caused by spatial configuration. The used SDs are product (thing/object) oriented and not including spatial adjectives. SD item sets in environmental psychology provide those (cf. [34]), e.g. SDs such as private-public, inviting-repelling, roomy-crammed are clearly space related. While it is our vision to develop a SD based questionnaire for pub-lic installations, which also accounts for spatial UX quali-ties, this is clearly beyond the scope of this study. A newly composed item set would require a new validation of the questionnaire, by running a PCA [36] to make sure bipolar adjective pairs are not ambiguous and separate in distinct dimensions.

Method

Repeated measurement with AttrakDiff

Our data collection was aimed at 20 completed question-naires per sampling point (180 total). We assumed that ask-ing the participant nine times for completion of the AttrakDiff questionnaire would frustrate and bore them; leading to impatience and data inconsistencies. In contrast to other studies which used the AttrakDiff questionnaire repeatedly [42] to measure how stable experiences are over time, our concern was that very short repetition (30-60sec.) times would lead to gradual lower ratings due to boredom. To avoid this, we decided a participant would only rate 6 out of 9 different sampling points, which required us to recruit 30 participants for each study. Furthermore, we ran-domized the item sequence as well as their polar orienta-tion. Finally, we expected that if participants become impatient (RQ2) this would result in larger standard deviation at the latter sampling points compared to the first.

Cross-Site comparison

The study was repeated at a plaza near the university library to either verify the results gained from the first study or identify environmental influences for divergent results. This particular location was chosen, because it provides a very similar spatial configuration to the first study. The front row sampling points are at the same distance to the projection, the back row is near to a wall, sampling point SP4 is in both settings close to open space. A major difference are the sampling points of the rightmost row (SP3, 6, and 9) being at an edge in study #1 in contrast to #2 (compare figure 1).

Procedure

The actual study was conducted on several days at night in winter with low temperature around 4°C. The participants were given a polystyrene foam cube representing a red square on a 5x5 grid (see figure 1, left). They were asked to practice moving the red square around by shifting the cube rapidly up, down, left or right and ‘pick up’ the yellow cir-cle by pushing the cube away from the body and ‘bring it’ to the opposite border of the grid. When they completed the task, the square was centered and the circle was randomly assigned a new position in the grid. The participants were allowed to practice till they felt confident in accomplishing the task. After that the participant was guided to the first sampling point where she was asked to carry out the task, and then rate the ten semantic differentials of a printed short version of the AttrakDiff questionnaire. This was repeated for 6 sampling points.

Results

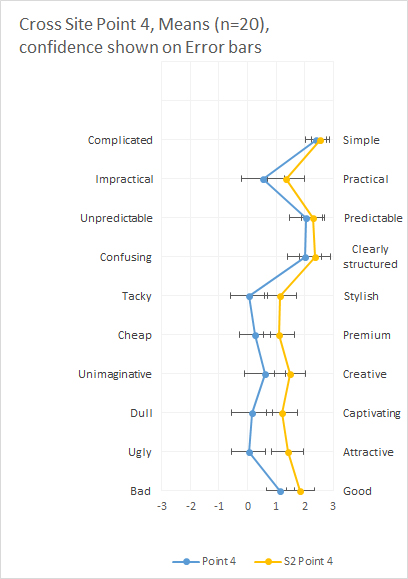

Due to the fact there was mostly no experiential difference (RQ1) of sampling points in study #1 and #2, we wondered whether sampling point 1 (to 9) from setting #1 would be rated similarly to the corresponding sampling point 1 (to 9) in setting #2. A Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed for each sampling point pair of the dimensions PQ, HQ and ATT. The test revealed a significant difference for the HQ score at sampling point number 4 (SP4) (H(1)=5.196, df=1, p<.05) and ATT at SP4 (H(1)=6.578, df=1, p<=.01). The pragmatic quality score for SP4 did not significantly differ, as all other points were not for scores of PQ, HQ and ATT. The differences in means of the individual items of HQ and ATT for SP4 can be reviewed in figure 3. It shows SP4 was rated more stylish, premium, creative and captivating in study #2 than in #1.

Discussion

One of our main concerns for the study was that very short repetition (30-60sec.) times of the AttrakDiff would lead to gradual lower ratings due to boredom (RQ2). In order to avoid this bias, we decided that participants would only complete the task at 6 out of 9 sampling points. This had the effect, we had to use a not that well known statistical test named Skilling-Mack test (a Friedman test when there are missing data). Due to missing data, there is no post-hoc test that could be performed if the Null-Hypothesis is re-jected. This is an issue especially if there are more differences found through the experiment than we encountered. In that way we were lucky that SPs did not differ that much. With our analysis of short termed repeated measure using AttrakDiff, we provide evidence that our concern was un-justified and we are somewhat happy to report so, as our concern only complicated the study. For future studies, we recommend testing participants against all sampling points as users do not become overly fatigued.

To understand why the sampling point 4 at the university library was significantly different from SP4 in study #1, we visited the site again and realized a bright spotlight illumi-nates a 6m tall sculpture casting a shadow near that area. This might be a reason for increased hedonic qualities. From prior studies, we know lighting has strong emotional effects for vistas at night times. They are not always posi-tive as in this case. However it is interesting to see that pragmatic qualities are not affected by this.

The absence of a significant difference is not a proof that positioning does not have an impact on user experience, as other stimuli might overshadow or dominate the experience of a user. Spatial experience is an inherently difficult sub-jective feeling to measure and the bipolar adjectives of the Short AttrakDiff is not fully tuned to expose those charac-teristics. However, our current assumption is that differences will be measured the more widespread (>15m away from the façade) sampling points will become (cf. figure below).

Reference:

Patrick Tobias Fischer, Saskia Kuliga, Mark Eisenberg, and Ibni Amin. 2018. Space is Part of the Product: Using AttrakDiff to Identify Spatial Impact on User Experience with Media Façades. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Symposium on Pervasive Displays (PerDis ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 5, 1–8.

Research Team:

Patrick Tobias Fischer

Saskia Kuliga

Mark Eisenberg

Ibni Amin